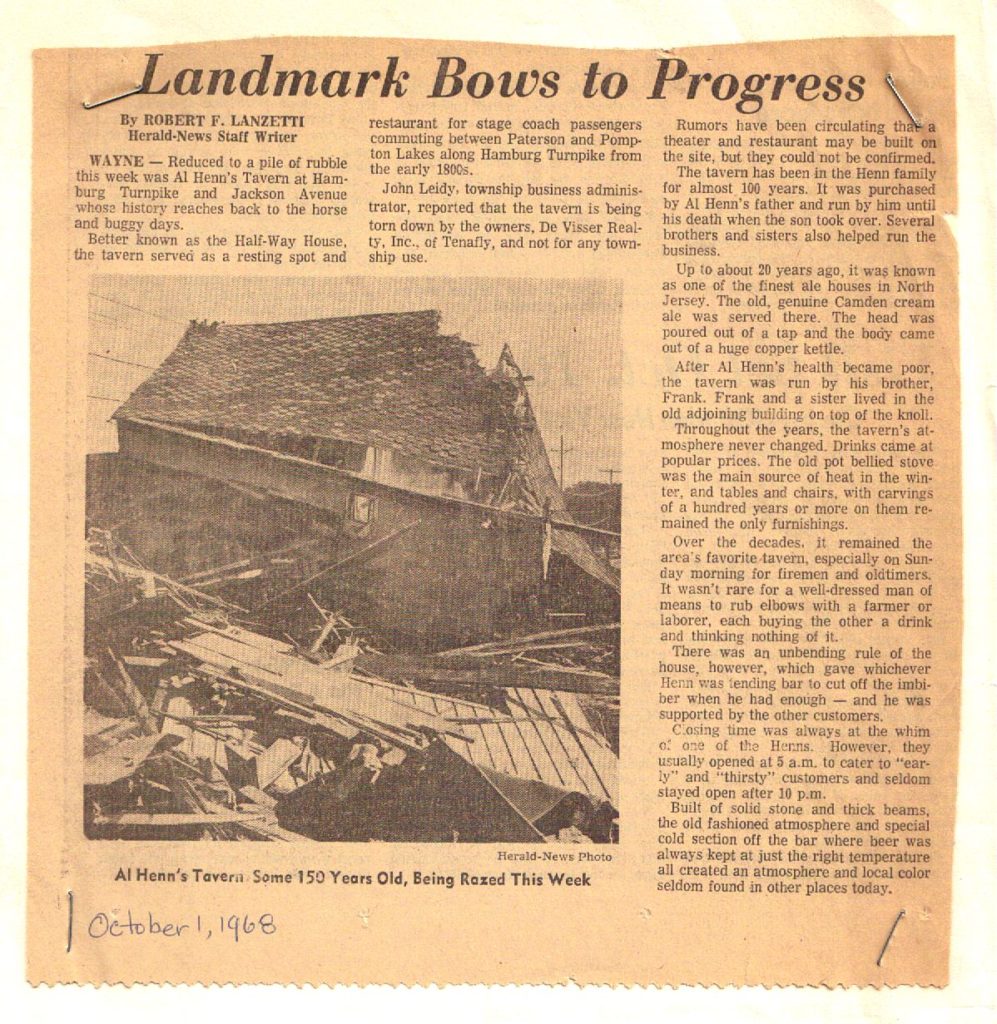

The third of three “Then & Now” photos I acquired a while back (here’s the first one and here’s the second).

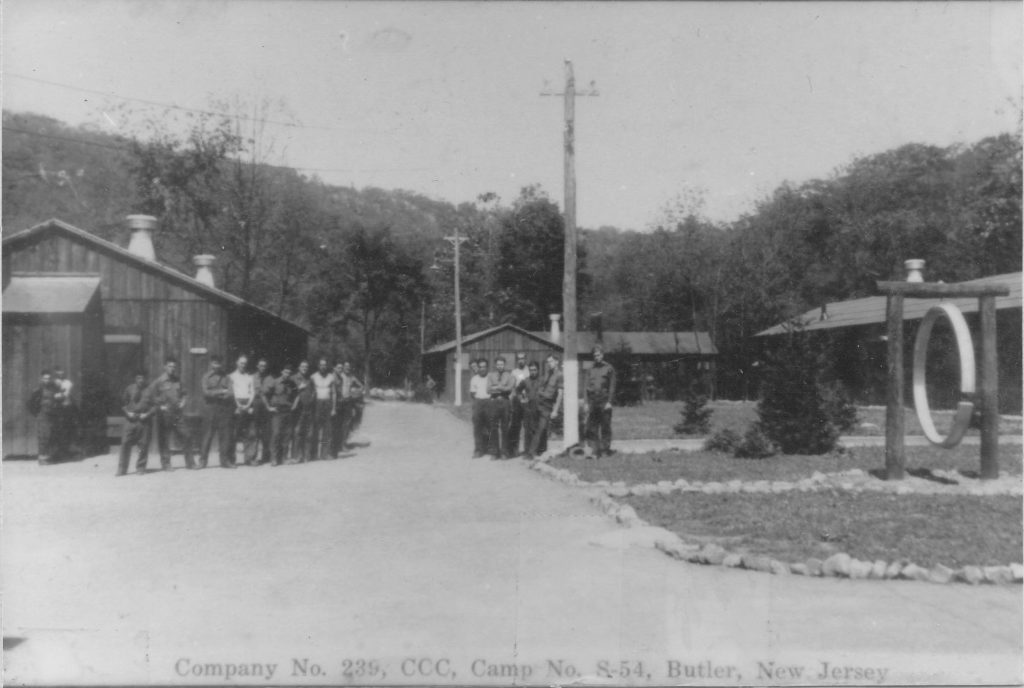

To quote the earlier posts, the origin of these is as interesting as their content: In 1940, someone stole the black-and-yellow “Railroad Crossing” signs at the two Butler crossings on the Paterson-Hamburg Turnpike. An employee of the NYS&W (New York Susquehanna & Western) railroad was sent to document the scene. Were the vandals caught? Doubtful. The signs were, however, replaced.

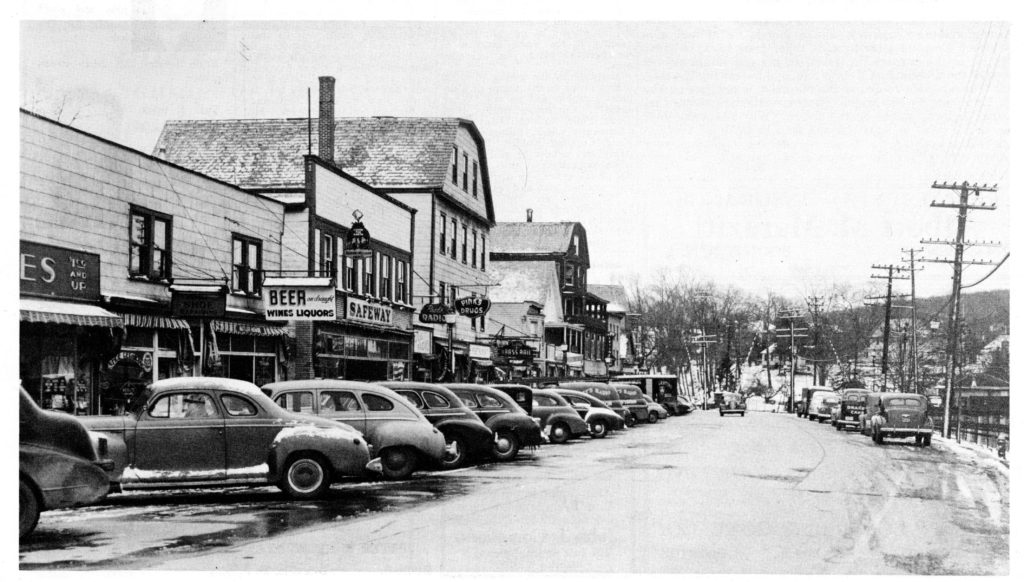

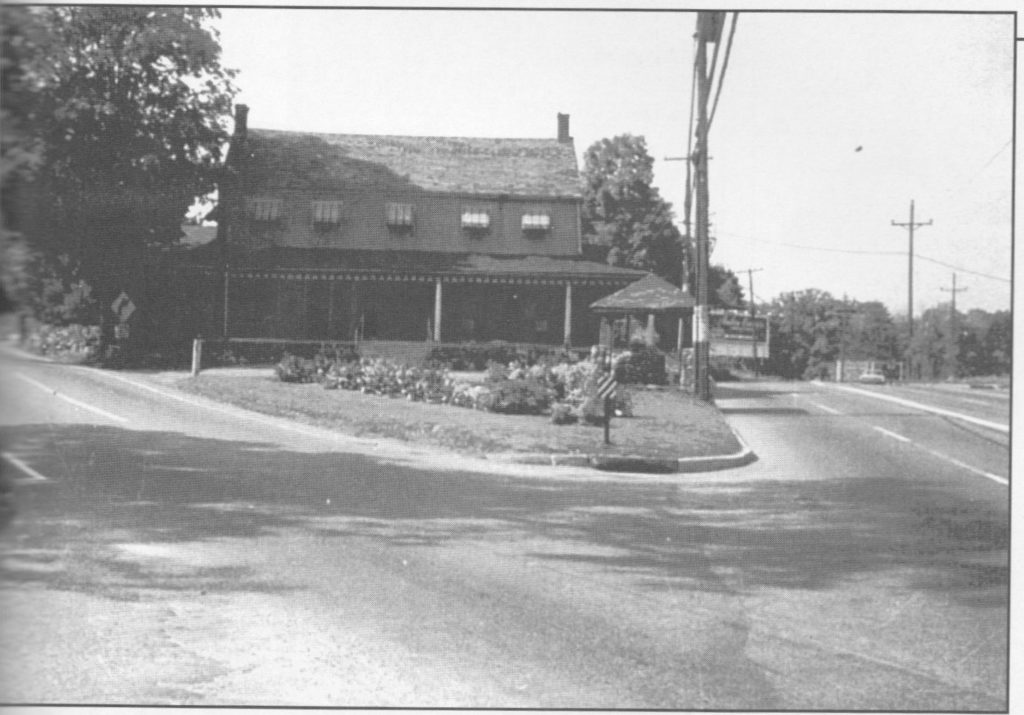

In this one, we’ve made a U-turn and are driving south. Between the two railroad crossings stands the venerable old business known then, as now, as Excelsior Lumber.

The full size photo is a real glimpse into the past. Look closely, and you’ll see that there was a railroad siding that ran behind the yard. The car is a late 1930s something (suggestions welcome).

At right is a Sunoco gas station. There are two gasoline pumps sporting glowing globes on top. The car appears to be 1920s. you can see the fellow who pumped the gas chatting with someone in the dump truck. The building was expanded into a full-service garage at some point, but the gas pumps are long gone.

Visible above the tree line is the original, really tall smokestack of the Pequannock Valley Paper Company (about half was removed when the mill closed). And straight ahead, just over the RR tracks, is a RR siding building that we saw in the first photo.

Here’s how this scene looks today.

What became of the classic black-and-orange signs? They probably graced the wall of the thieves’ garage or rec room. Were they ever caught? Was the theft responsible for an accident? I did not find any mention in the old newspapers; perhaps a railroad buff might know more.

And that’s our tour! If you enjoyed the drive, I hope you’ll let me know in the comments.

-30-