Harvesting, storing, and selling ice was a major industry from before the 1800s until the late 1940s, when refrigerators became common in the home. Every lake and pond that could produce a decent quantity of ice was harvested all winter. In our region, that included the rural areas of Lake Hopatcong, Greenwood Lake, Charlotteburg Lake, Echo Lake (also known as Macopin Lake, Lake Macopin, and Macopin Pond), and the topic of this post, Greenwood Pond in the Oak Ridge section of West Milford.

Ice was a major source of employment. Companies would hire as many men (and teenaged boys) as they would need, as well as farmers and their horse teams who were idle during the winter. In warm weather, route men were needed to supply homes and businesses with the ice harvested in the winter. Ice was always needed by homes, hotels, and other businesses in the cities and vacation areas.

Winters were colder two centuries ago; ice would form by November, growing to over a foot thick, and still be available for harvest as late as mid-March.

Around 1897, Edward R. Greenwood founded what would become a prosperous coal business in Paterson. Two years later, he started a new venture, the Silk City Ice Company, alongside his E.R. Greenwood Coal & Ice Company. Initially, he imported ice from the Poconos. Wanting a more local source, around 1907 he purchased Greenwood Pond and surrounding lands, and constructed a dam to enlarge the pond. The pond and the dam still exist on Bonter Road (which was then called Icehouse Road), not far from Oak Ridge Road.

Greenwood built a large ice house ideally located between the shore of the 4.5-acre pond and the NY Susquehanna & Western (NYS&W) railroad line. A siding brought railroad cars alongside the ice house to be packed with ice cakes bound for Paterson.

A typical ice house would be quite large and several stories tall. Greenwood’s was perhaps 50 by 150 feet, between 40 and 50 feet tall. Echo Lake had one, as did Lake Hopatcong, while Greenwood Lake boasted two, both owned by the Hewitt family.

They were all built the same way: the outside walls were built of wide boards, and another such wall was constructed on the inside. An ice house would be divided into several rooms, with the dividing walls built the same way. The gap between them was filled with sawdust for insulation, while salt hay was used in the individual rooms.

Ice harvesting was grueling work. Teams of men would work 10- to 12-hour days; they were well-paid and, at some ice houses, also well-fed. At Greenwood, an early-morning steam whistle signaled that the ice was ready for harvest. Between 30 and 40 day workers would congregate at the pond as a crew would plow any snow off the ice. One team would carefully score a checkerboard pattern in the ice; this was necessary to ensure uniform ice blocks. Other teams would begin the cutting process. Originally the ice was manually sawed into long blocks using specially-designed saws. By the 1920s, gasoline-powered ice saws replaced that manual labor. (A gas-powered ice saw is on display at the Long Pond Iron Works in Hewitt, NJ.) The men would break for coffee as well as a hearty lunch.

The ice blocks were floated to a long conveyor belt where they were cut into cakes; a steam-engine-powered conveyor lifted them into the ice house where they would be stacked among the rooms. It might take several days to fill the Greenwood icehouse, while the two much larger icehouses at Greenwood Lake might require weeks.

is to the right.

All ice houses needed a delivery system for their product. Before the advent of railroads, much was packed into canal boats and sent down the Morris Canal. By the 1830s, railroads were much faster and could handle much more product. The same railroads that delivered vacationers to idyllic spots such as Brown’s Inn in Newfoundland could return to Paterson with a profitable payload. Greenwood Pond had a siding constructed to the railroad line just yards away, while Echo Lake had a dedicated, 1.5-mile railroad line (the Macopin Lake Railroad) connected to the NYS&W.

Once packed with ice blocks, the railroad would take the ice to various destinations for delivery. Greenwood didn’t market his ice in Oak Ridge, but local people, and some shop keepers, would come to the ice house to purchase bags of ice chips that resulted from shaping the ice cakes.

Silk City Ice sold ice in quantity to big hotels and such, but also maintained eight local routes in Paterson and Totowa. Each of the eight route men had his own horse-drawn ice wagon from which to sell ice to housekeepers and small stores.

Newspaper accounts paint a portrait of a fair and generous boss:

E.R. Greenwood, coal and ice dealer of this city, gave a theatre party and banquet to his employees and their wives as a means of expressing his appreciation of the good work done by the men in harvesting the ice crop, during which time they labored day and night.

After watching a play at the Lyceum theatre, the party partook of a well prepared supper in a local restaurant. The ladies were presented with large boxes of chocolates, while the men received cigars.

Paterson Morning Call, 01 Feb 1917

In late 1920, Greenwood turned over the retail route business of Silk City Ice to eight of his long-time faithful employees. According to a 1920 newspaper article, he realized that the present cost of living was a constant worry to the man working for wages. In turning over the business to the route men, he set each up as an independent business man whose earnings would depend entirely upon the efforts he put into the business. Each man also was gifted the wagon each had been using, and had their names painted on the sides. The ice would continue to be harvested in Oak Ridge.

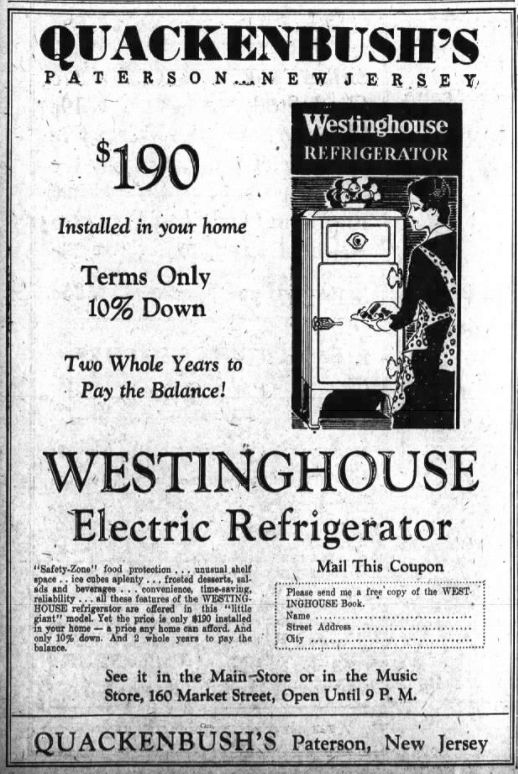

By the 1930s, however, the writing was on the wall for the ice harvesters. The invention of the refrigerator, and the introduction of “artificial ice” made in commercial freezers at ice plants, would soon doom the ice-harvesting industry. “Mechanical iceboxes”, which used a liquid refrigerant to produce cold, had been invented in 1915 as an add-on to the traditional icebox. By the mid-1920s, the modern refrigerator was available for purchase, but only the wealthy could afford them; it would take decades before they became affordable to many families.

Apparently, harvesting came to a close in the late 1930s, and the ice house was abandoned. Eventually, it collapsed; the wooden structure has long since returned to the earth. The railroad siding is long gone. The concrete foundation and footings, and some iron hardware, however, still survive, bearing mute testimony to a bygone industry.

Photo Credits: Dale Greenwood Dunn

Various details: Recollections of a New Jersey Ice Harvest by David W. Dunn, Jr. (2014) and my own research.