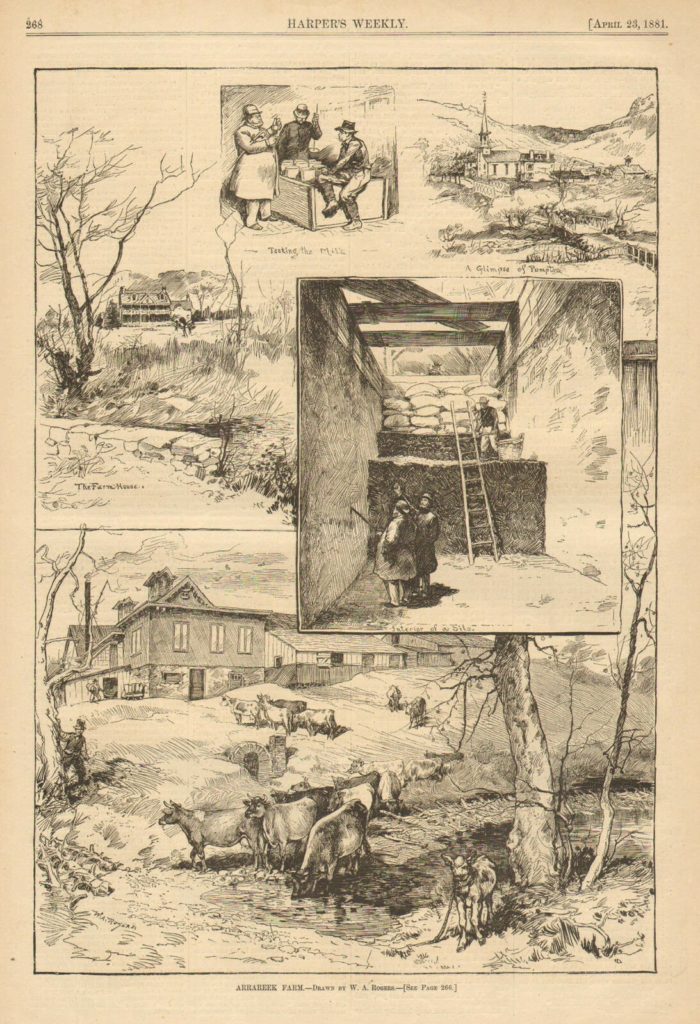

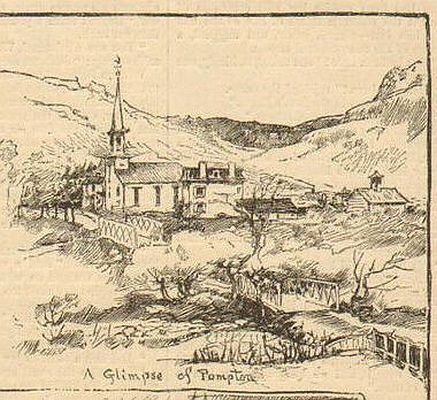

My interest in Arrareek started with a print from an 1881 issue of a very popular 19th-Century magazine titled Harper’s Weekly. It depicted some farm scenes, but also a church I recognized right away, in a view that in some respects hasn’t really changed much since then.

That’s the Pompton Reformed Church. It sits, as it has since 1814, on the Paterson-Hamburg Turnpike in Pompton Lakes at Ringwood Avenue. (It was spun off from the First Reformed Church of Pompton Plains, but that’s another post.) That was the clue that got the ball rolling.

In the late 1800s, a Newark grain merchant named Clark W. Mills owned a farm he called “Arrareek” in the rural farming village of Pompton, NJ. In 1876, starting to experiment with hybridization of Jersey corn, he grew 13 acres of Southern corn, but began to worry when he realized that it would all likely be ruined by frost long before it would ripen. Unwilling to see it all go to waste, as Harper’s Weekly put it, “he remembered the old method of keeping roots in mounds of earth, practiced from time immemorial.”

Ensilage

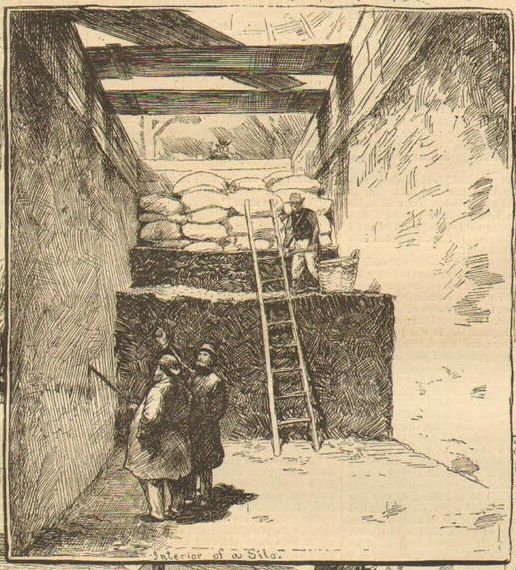

Mills’ method employed silos to store his fodder — but not the tall, round structures we usually think of. These were subterranean silos.

Mills instructed all hands to dig two deep pits in the dry gravelly soil inside his barn. In each silo a layer of short, cut lengths of the Southern corn was laid on boards, which were then roofed with planks and compressed with bags of grain. Layer upon layer was added, and the compression allowed a lot of fodder to be crammed into each silo. It also allowed air and moisture to escape, which largely prevented the fodder from fermenting. As a silo was filled, it was also covered by earth. The fodder was then removed as needed throughout the winter.

This worked better than Mills could have hoped. Most of the corn remained edible, and his cattle thrived. Mills had, on his own, unwittingly rediscovered the ancient practice of “ensilage.” By 1880 he had perfected his innovation, and word of his success began to spread. He received more inquisitive letters than he could answer; reporters and the curious would visit, resulting in a lengthy piece in the April 23, 1881 Harper’s (accompanied by a full page of illustrations) and an equally effusive article in an early 1881 Journal of the American Agricultural Association, which titled Mills “the prophet and pioneer of ensilage.” Several out-of-state papers also wrote similarly admiring articles.

Harper’s reported that Mills’ 120 head of cattle and 12 horses “ate of it greedily” all winter long. Not only had he demonstrated a means by which to thriftily feed his herd at a substantial savings over hay, but his fat and contented cows produced “a large quantity of milk, the demand for which is so great that it is beyond his capabilities of supply.”

It’s difficult to overstate the impact of Mills’ innovation; it was a real game changer in the farming world. Mills’ ensilage method became a subject of keen interest to farmers nationwide who began to adopt it, including Abram S. Hewitt on his 1,000-acre farm in nearby Ringwood. While the method would preserve any fodder, Southern corn was far less expensive than hay.

This is the full page of illustrations from Harper’s Weekly. It shows the expansive Mills farmhouse and barn, in which were two silage pits 13 feet by 40 feet, and twenty feet deep. To see it larger, click it.

But Clark Mills’ newfound fame didn’t just benefit cattle farmers. Harper’s included flowery paens to the natural beauty of the Ramapo Valley, proclaiming “There can be no more beautiful country than that found in Passaic county, New Jersey, in the neighborhood of Pompton.” As word spread, more people came to make Pompton their home.

Finding Arrareek

But enough about ensilage! So just where was Arrareek? An 1882 piece in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle described it thus:

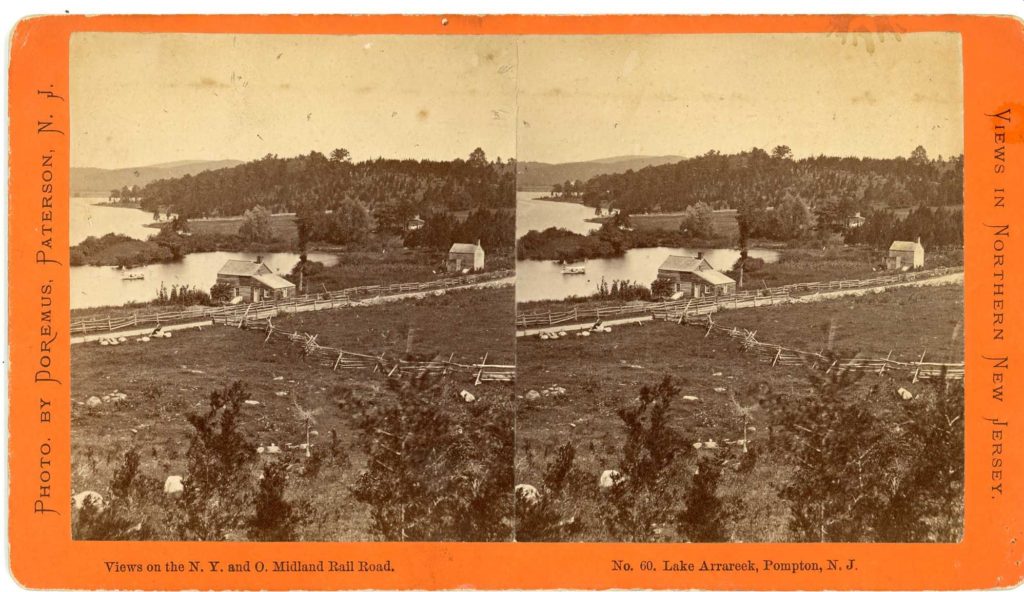

“On Arrareek Lake, a beautiful sheet of water, on which is part of Mr. Mills’ farm, resides the celebrated Mary Virginia Terhune, better known as Marion Harland, the author of a number of popular novels, and who during the present year celebrated her silver wedding at this pleasant summer home.”

“Arrareek Lake”? A search of the internet found this stereo postcard of that lake. (Click it to see it larger.) It could only be Pompton Lake. I’m not sure just where on the lake one can get this view; if you might know, please leave a comment.

As those familiar with Pompton area history would know, Mary Terhune was the mother of celebrated author Albert Payson Terhune. This description refers to (what would later be called) Sunnybank, located by the southeast corner of Pompton Lake. But there were more clues in this Lancaster PA publication:

“Just beyond Arrareek Farm you see the continuation of the plateau as it breaks through the blue hills and extends far beyond. …on Arrareek Farm there are two fairly big rivers, the Wynokie [Wanaque] and Ramapo. …right by Arrareek Farm stands an ancient stone house, which tradition states was once General Washington’s headquarters in 1777, for the old Pompton road was the back route on the line of communication between Trenton and West Point.”

So Arrareek was between the Wanaque and Ramapo Rivers, which narrows it down, and the “ancient stone house” on “the old Pompton Road” surely sounded like the Yellow Tavern. Also known as the Yellow Cottage, it stood on the site now known as Federal Square.

Those clues led to an 1877 map of Pompton. It was easy enough to find the Mills farm; it was quite expansive, encompassing some 290 contiguous acres of prime Pompton Lakes land. To see the map larger, click on it.

Clark Mills’ land holdings extended east from the Wanaque River, past today’s Federal Square, across Hamburg Turnpike to the end of Passaic Avenue, before turning south to about where Tudor Drive is today. From there he also owned a wide strip all the way to Pompton Lake (“Ramapo River” on this map). A person sitting comfortably on the front porch of the Mills farmhouse probably enjoyed the view accorded in the “glimpse of Pompton” illustration at the top of this post.

A neighborly feud

One of Mills’ neighbors was James Ludlum, the principal proprietor of the Pompton Steel Works, located on the Ramapo River just downstream of the falls. They shared a boundary west of the river (not shown on the map above), which seems to have led to some disagreements. A news item from 1883 tells the tale:

The residents of Pompton, N.J., were favored with a novel sight on Wednesday evening. It was the Sheriff of Passaic County driving sixteen cows along the road through the pouring rain. For some time there has been unfriendly feeling between Assemblyman Clark W. Mills and James Ludlum, the principal proprietor of the Pompton Steel Works,

Mr., Ludlum charged that Mr. Mills’s cattle trespassed on his domain. Finally sixteen of Mr. Mills’s cows were caught and locked up in Mr. Ludlum’s barn. Mr. Mills got a writ of replevin, armed with which Sheriff Winfield Scott Cox proceeded to Mr. Ludlum’s place on Wednesday and took possession of the distrained cattle.

There were sixteen cows, and it was dark and raining hard as the highest official of the county of Passaic with his consignment of beef proceeded “on the hoof” to Mr. Mills’s farm. Sheriff Cox, however, was raised in the country, and knowing something about cows, he got them safely to their owner’s barn.

New-York Tribune, 29 Jun 1883

And, finally, what is the origin of the name “Arrareek”? This is all I could find:

“…there were no Indians formally known as the ‘Arareeks’ [sic], but the name appears in an ancient deed, in which, as he recollected, the Pompton Falls or the land immediately about the same, was so designated. Any Indians, and there must have been very few, if any, living about Arareek, would be naturally designated by the name of the place.”

Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, 1913

Perhaps Mills knew about that “ancient deed” — he might even have owned it — and liked the name enough to resurrect it from the dustbin of history.

More than a farmer

In addition to being an ensilage pioneer, Clark W. Mills had a few other accomplishments to his name. In his occupation as a well-known grain broker, he and/or his partners were granted several patents in the 1860s and 1870s for improving the cooling of grain after being dried, as well as “a certain new and useful Improvement in Floating Grain-Elevators” for transferring grain from canal boats to a storehouse or vessel.

Mills also served, at various times, as the Chairman of the Township Committee of Pompton as well as Chairman of the Board of School Trustees. He also represented the first district of Passaic County in the NJ Assembly from 1883 to 1884. There’s a page of info about him, his wife Julia, and their eight children at the Familysearch genealogy site.

Arrareek today

Clark Wickham Mills died at Newark, aged 54, on January 5, 1887; his lands were sold a year later for $18,000. Nothing of Arrareek survives today; the house, the barn, the silos are all long gone. As the village of Pompton Lakes grew, due to the rapid growth of local employers like the German Artistic Weaving Company and the Smith Powder Works, farms and fields disappeared, streets were constructed and homes sprang up where corn and wheat once grew.

But some of his land along the Wanaque River was preserved as open space and parkland, stretching from Hamburg Turnpike (the “old swimming hole”) to Herschfield Park. It’s a lovely area that has been long been popular with young and old for decades. As Harper’s described it, “There can be no more beautiful country than that found in Passaic county, New Jersey, in the neighborhood of Pompton.”

-30-